Machu Picchu is the superstar among Peru’s ancient ruins. A photograph of Machu Picchu is enough to conjure an immediate “I want to go there” thought, but the visual grandeur of these ruins are just half the appeal. An understanding of the history of why Machu Picchu was built and information about its Inca creators add to the allure of these ruins and enhance your visit.

Pre-Columbian

Scholars have estimated that Machu Picchu was built around 1450 A.D. This places the construction of the site under the rule of Pachacútec, who was also responsible for building Sacsayhuaman as well many other remarkably important Inca structures and urban complexes, and otherwise expanding the frontiers of the limited Inca state beyond the boundaries of the Southern highlands – turning it into the Empire Incas are known for. In fact, it has been suggested that the site itself was a Pachacútec’s private property – part of the “royal estates” that were assigned to ruling Inca families or panacas upon the rise of a member to the “throne.”

Machu Picchu was far from being a secret place and therefore was definitely not the “lost city” that Spaniards were seeking. Its geographic location and strategic position turned the place into a main gateway for connecting the upper highlands around the immediate Cusco region with the lowlands and rainforest. As it is well known,much of the success of the Inca state was based in its capacity of fostering trade among distant posts of the Andes, hence mastering the ecological control of what has been called a “vertical archipelago” – meaning the varying altitudinal layers of production that conform the Andes – and therefore guaranteeing access to multiple products coming from different regions. Therefore, building a site that represented political centralization, organized religious practices, systematized production of crops, and at the same timed provided semi-permanent and permanent lodging for transiting and colonizing communities, in such a pivotal location was deemed crucial.

Agricultural terraces once used by the Incas can be seen en route to Machu Picchu.

Agricultural terraces once used by the Incas can be seen en route to Machu Picchu.

Photo by Richard Vignola/Flickr

The building of the site still remains as a matter of controversy. While many stories have been deployed to explain the architectural and hydraulic achievements of Machu Picchu, what seems indisputable is the use of tributary communities from neighboring regions seasonally mobilized to transport much of the stone used in the building process. This stone is mostly white graphite, and came from quarries located a few hundred meters below the actual location of the complex. The stone was shaped with bronze instruments and polished with sand, which made the process more labor demanding.

Machu Picchu was mostly inhabited by seasonally stationed colonizers and temporary settlers, which were known as mitmas. Mitmas were largely responsible for the agricultural success of the entire Empire: these tributary populations traveled across all territories under Inca rule, working in agricultural lands of different populations that at the same time became part of the Inca state, and hence fostered centralized production – part of the crops remained locally, but an significant amount went to the Inca – making the central economy of the state remarkably powerful. Machu Picchu was therefore a laboratory that grouped together all the basic state tools that made the Inca state the most important polity of the pre-Columbian Andes.

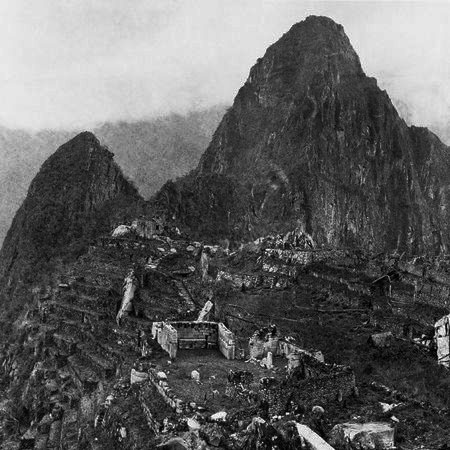

Machu Picchu upon arrival, before the cleaning process.

Photograph by Hiram Bingham, 1911

As it is also well known, production and religion were – and some might say still are – intimately linked. Thus it is no surprise that another important use of Machu Picchu was worshiping. The site also preserves clear signs of having been used as a major sanctuary. Scholars indicate that special women – called acllas– were raised and educated in Machu Picchu and remained there devoted to supplement agricultural activities with the much-needed spiritual framework. In fact, out of 135 human corpses recovered from the archeological work, more than one hundred belonged to women of a seemingly young age.

This also indicates seasonal populations were not as present during times of decline and final abandonment of the complex, something that posits more questions than answers. Specialists again speculate that royal estates faced decline when the ruling Inca died, and such was the destiny of Machu Picchu. By the end of Pachacútec’s rule (1471), and the rise of Túpac Inca Yupanqui (1471-1493), a member of a rivaling panaca, Machu Picchu was progressively abandoned and solely remained as a retirement place for members of Pachacútec’s family. At this point, the site gradually lost preeminence amidst trading and worshipping posts of the Inca state. By the time of the arrival of the Spanish conquistadors little was known about the the importance Machu Picchu once held, and its memory became lost in the narrative of the conquest of Peru.

Colonial

Interior of one of the buildings of Machu Picchu, detail of the windows.

Interior of one of the buildings of Machu Picchu, detail of the windows.

Photograph by Hiram Bingham, 1911

Machu Picchu was probably “abandoned” somewhere in between 1534 and 1570, years in which the Inca state faced conquest and offered some resistance. The crisis unfolded by the early years of colonial rule allowed remaining mitmas to run away from the site. By the same token, its somewhat hidden position turned Machu Picchu into an ideal shelter for escaping Spanish armies and organizing rebellion. The so-called “Incas of Vilcabamba”, the last political representatives of the declining Inca state, led first by Manco Inca and later by Túpac Amaru I, probably gathered at Machu Picchu and launched campaigns of military resistance against the invaders. When the resistance was finally repressed, Machu Picchu would have become part of the larger properties of local curacas, local leaders eventually co-opted by colonial power to collect tribute for the Spanish, but otherwise lost its original purpose.

Kitchen utensils found at the interior of buildings.

Photograph by Hiram Bingham, 1911

There is much speculation about whether the Spanish visited Machu Picchu in colonial times. Documentation about tribute from the Urubamba region includes a narrative about the “Picchu brook”, though this tribute was being collected by local encomenderos and corregidores from the neighboring town of Ollantaytambo. It is unclear whether the Spanish ever ventured themselves deeper into the Urubamba valley and found Machu Picchu. Other researchers have suggested the place was used as a rehearsal site for launchingthe campaign against “idolatry” – this is the colonial Catholic effort to extirpate pre-Columbian rites and beliefs and enforce orthodoxy – due to the archeological evidence of bonfires. Furthermore, these campaigns of extirpation of idolatries would be responsible for taking away the pre-Columbian artifacts that remained in the city after its abandonment. At any rate, whether the Spanish found Machu Picchu or not, the site never became a space for permanent colonial settlement in the way other royal estates did – such as Ollantaytambo and areas within the urban limits of Cusco city. As decades went by, references to Machu Picchu or its area became increasingly elusive and rare, to the extent that its existence was almost completely forgotten aside from a handful of local stories about a “lost city.”

Modern

While Machu Picchu’s existence was indeed ignored or rather neglected from official accounts of Peruvian history, local people did keep a memory of the site, its location, and its importance. These locals called the attention of nineteenth-century expeditionaries like Antonio Raimondi and Augusto Berns. In fact, some accounts claim that Berns did manage to find the ruins and would therefore be the actual “discoverer” of Machu Picchu. Yet no physical evidence or report of the presence of these travelers on the site exists.

By the early twentieth century, a local landowner named Agustín Lizárraga reportedly found Machu Picchu and engraved his name on the wall of the Temple of the Three Windows. While the engraving was apparently removed afterwards, another traveler of American origin – Yale history Professor Hiram Bingham III – took Lizárraga’s stories seriously and traveled to the Urubamba valley. It was 1911, and Bingham was already in the Cusco area looking for the ruins of Vitcos, which according to the scholar would have been the last Inca capital in Vilcabamba. Aided by Melchor Arriaga, a local sharecropper, and a local police officer commissioned by the Peruvian state, Bingham made his way from a plantation close to Machu Picchu called Mandorpampa – after six days of traveling through the valley – and found the first traces of what seemed to be, in his own words, “the largest and most important ruin discovered in South America since the days of the Spanish conquest.” It was noon of July 23, 1911, and Machu Picchu had been (re)discovered and unveiled to the world.

Bingham informed Yale University about the potential of his discovery. Likewise, he requested aid from the National Geographic Society and permission from the Peruvian government to start the necessary archeological work. This work started barely three weeks after the discovery, when Bingham requested the help of H.L. Tucker and Paul Baxter Lanius, both engineers of the 1911 expedition, to draw the first map of the site. The result confirmed what Bingham had initially thought, the site was of pivotal importance: in fact, the constant presence of windows in most buildings led him to believe Machu Picchu was in reality Tampu Tocco, the mythical site where the Incas had originally emerged according to one of their foundational stories. Archeological work in Machu Picchu took place between 1912 and 1915, time in which the entire site was cleaned from brushwood and scrub that covered most of the structures, most areas were excavated and artifacts were registered and classified, and all the evidence was sent to Yale University for conservation. In 1913, National Geographic published a major report about the discovery and the unveiling of Machu Picchu was official.

A present-day view of Machu Picchu.

A present-day view of Machu Picchu.

Photo by Boris G./Flickr

Throughout the twentieth century, Machu Picchu progressively acquired a preeminent place in national and international tourism. By the mid-twentieth century, there were many debates about the preservation and conservation of the ruins framed within a larger discussion about the situation of contemporary indigenous peoples in Peru. These debates eventually found room at the international level, and UNESCO included Machu Picchu in the list of the World Heritage Sites in 1983. Since 2007, Machu Picchu has become one of the New Seven Wonders of the World. The site has been a main source of pride for Peruvians, and its figure is a symbol – portrayed in bank notes, coins, and different logos – of the greatness of Peru’s history.

Learn more about Machu Picchu here.

Experience a tour to Machu Picchu

Explore our tour packages to Machu Picchu and contact our team of experts to help plan your trip.

Former guide with Peru for Less and now professor of Latin American and Latino/a Studies at a college in the United States, Javier contributes his endless knowledge of Peru’s past and present.